Anki isn’t just for memorising facts! What is Anki -> debunking Anki myths -> what is learning, knowledge, intelligence?

Original publish date: 2021-09-06

Summary

'Anki is just

for memorising

facts') id2(Quick anki

primer) a1(Daily

flashcard

process) a2(Creating

flashcards) a3(Contains the

3 components

of effective

learning) id3(What is

learning,

knowledge,

intelligence?) l1(Learning:

3 steps) l1_1(Encoding) l1_2(Consolidation) l1_3(Retrieval) id4(Bloom's

Taxonomy of

Learning) b1(6 Categories

of Learning) b1_1(Anki covers

at least

first 2) b2(4 Categories

of Knowledge) b2_1(Anki covers

at least

first 3) id5(Inert vs

activated

knowledge) id6(Prior knowledge

as foundation

for new

learning) id7(Intelligence) i1(Fluid) i2(Crytallised) id1 ==> id2 id2 -.-> a1 id2 -.-> a2 id2 -.-> a3 id2 ==> id3 id3 -.-> l1 l1 -.->l1_1 l1 -.->l1_2 l1 -.->l1_3 id3 ==> id4 id4 -.-> b1 b1 -.-> b1_1 id4 -.-> b2 b2 -.-> b2_1 id4 ==> id5 id5 ==>id6 id6 ==> id7 id7 -.-> i1 id7 -.-> i2

Introduction

With this website, I’m aiming to share the essentials of “meta-learning”, the field of learning about learning, in order to help empower people to increase their ability to learn and form knowledge. I used to feel incredibly daunted by new fields, but now feel completely empowered to gain deep understanding of new topics at a much improved pace to my old methods. Meta-learning also ensures that you retain your learnings over the long run, meaning you can engage in “cumulative” learning, which is a huge gain from the “sand spilling from your hands” feeling I had re: learning during University.

In the field of meta-learning there are a bunch of empirically demonstrated methods for how to learn, how to retain information, and how to gain deep understanding. The shocking and literally thrilling thing is that the free & open source tool Anki contains most if not all of these techniques. I feel silly in a way with how much I talk about Anki and how it’s really all I think you need to supercharge your learning, but it really is. Onwards!

See the footnotes for this post here.

“Anki is just for learning facts”

For those who have heard of Anki but haven’t used it, I believe there’s a common thought (based on conversations with friends, comments on the internet, and feedback I received when first sharing this website with people) that Anki is good, but it’s really only for memorising things, for learning static facts, etc. We live in a time where memorisation/ learning by rote either just isn’t part of what we’d consider part of the toolkit of learning, or something that is actively looked down upon. As briefly argued in my first post (and heavily supported by the science and meta-learning practitioners), memorisation is actually one of vital components of learning, knowledge formation and intelligence.

I’m therefore here to argue that Anki is actually the most powerful way to improve knowledge, understanding, and even what constitutes intelligence. It’s a profound example of a tool for thought that allows us to greatly increase our capacity to learn via the use of computers.

I’m going to be pulling heavily from the book Make It Stick as well as my own experience of using Anki for years.

A note re: my learning workflow: I also use a tool called Obsidian (similar to Roam Research but open source and (whisper it) better) which is the other vital part of my learning framework. However, Anki is where the vast majority of true learning & knowledge consolidation occurs (whereas Obsidian is more for note taking and acting as a “second brain”). The two represent the “inert vs activated information” idea that I’ll touch on later.

This article is going to be an attempt to collect all the relevant topics/ concepts in a semi-structured narrative: whilst I’d love to take the time to really hone the ideas, I a) have limited free time outside of work and b) really want to get this stuff written down in relatively coherent but unpolished way to let me move onto other parts of this project (you should see the to do list for this site!!). There are loads of relevant things to cover. It’s worth saying that none of this is my own research: I’m just synthesising a few sources[1] into one guide along with my own experiences and learnings. The fact that I’m so excited about sharing this stuff is a testament to just how profoundly powerful I think this all is, and I’d really encourage you to give it a try.

A really quick (< 1000 words) primer on Anki

Before getting too deep into the weeds, here’s a really quick view on what Anki is and how you use it, just to give some context for what will follow.

The basics of using Anki

(Note: post 3 on this site is a concise user guide to Anki, covering everything you need to get started + all the key tips I have and things I wish I knew when I started out)

What is it

In brief, Anki is a free, open-source digital flashcard app, with a really healthy community.

You make bespoke digital flashcards (you can also download shared ones, which has pros and cons[2]), and then you review them every day. (Note: the iOS app costs ~£18, but is totally worth it)

A look at my (kind of messy) collection of decks (after 12 minutes of reviewing, leaving only 2 left to do)

The daily review process

By default, you’ll see 20 new cards a day (if you have that many new & unseen cards), although you can tweak this (for example Medicine students will set it to the max).

You can have multiple decks, i.e. one for a certain book, one for vocabulary etc. You can then tweak the settings for each: I’ve got a huge english vocab one and I’ve set it to only show me one new word per day so I don’t get overwhelmed.

Anki provides a queue for you each day i.e. the algorithm has worked out which cards are ready to be reviewed. For context, as someone who has added cards at varying levels of volume throughout the years, I now average around 80-120 cards to review per day, which takes me 10-15 minutes. I tend to do this in one go at my laptop, but you can also do bits here and there i.e. whilst on the bus, whilst brushing your teeth etc.

You rate each card as you go based on how easy or difficult it was to remember.

If you found it easy, the gap until you next see the card will be longer, whereas if it was hard to recall, you’ll see it sooner: if you couldn’t remember it at all, you’ll see it again tomorrow.

This relates to spaced repetition and the forgetting curve.

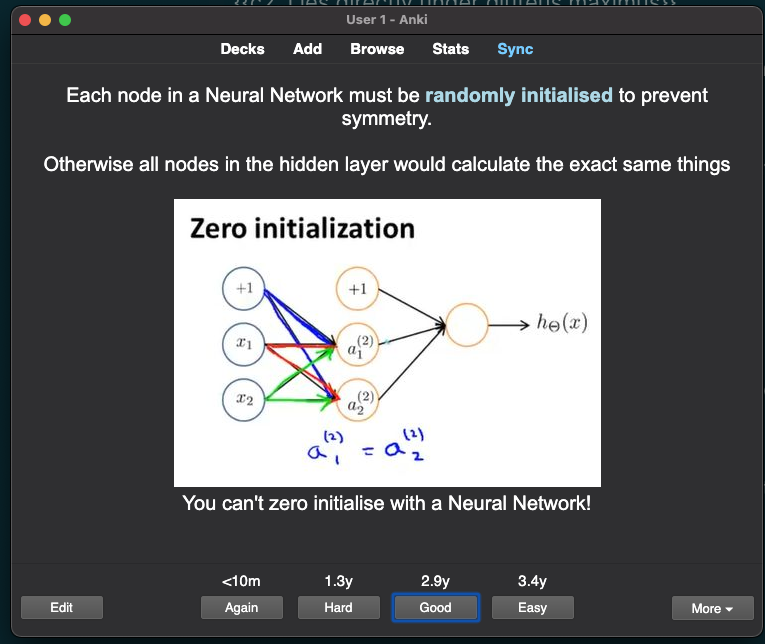

Cloze deletion - fill in the blank

Note: here, I’d rank this card as “good” as I recalled it well. As this is an old card, I now won’t see it again for 2.9 years!

Creating flashcards

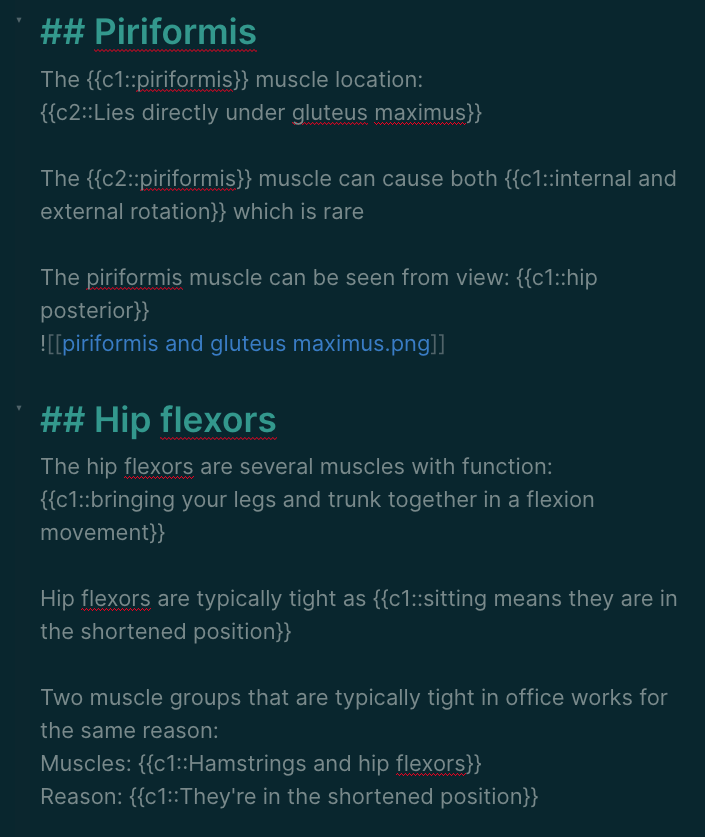

The most recommended card type to make is called a cloze deletion: it essentially leads to “fill in the blank” cards. For example:

{{c1::Toby Ord}} is the author of {{c2::The Precipice}} Will lead to 2 cards being made, one that shows “__ is the author of The Precipice”, and one that shows “Toby Ord is the author of __”. A keyboard shortcut can be used to populate the {{c1::}}, making this a really quick card to make (although as I’ve briefly argued based on my experience after reading Andy Matuschak’s “how to write good prompts”, making flashcards first in a plain text file rather than directly in Anki is a much better approach as it allows a holistic view of what has been made, what else could/ should be made, etc).

Making flashcards in a plain text document is the biggest improvement I’ve made to my Anki workflow in the years I’ve been using it

Cards can have images embedded in them to aid with memory, and there are some key patterns to use to make good ones. I’ll be sharing these more in the next post, but here’s an essential list of 20 tips by the creator of SuperMemo, an Anki competitor. And if you’ve got time, this article by Michael Nielsen is an absolutely incredible primer on this field and has some great insights into card patterns and antipatterns.

Whilst I’ve mentioned that there are patterns to make good ones, and on the flip side you can definitely make bad ones, I’d highly encourage you to get stuck in without worrying too much about this at first. It could feel daunting to act on the 20 tips from Piotr Wozniak immediately, but in my experience I worked a lot of them out in the course of making cards, reviewing them and realising that I’d made some errors in creation (i.e. too vague, to complex etc). Whilst using these rules early can save you pain down the road, I wouldn’t want to make creating cards sound too complex and thus put people off giving it a go ASAP. That being said, the sooner you do start making good cards, the less mad you’ll be at your old self: I still have cards that appear and stun me with how badly I worded them etc.

Why Anki is so great & basically the only learning tool you need

Anki (and other “spaced repetition software” (SRS) like SuperMemo) contain most-to-all of the key ingredients for effective learning that are recommended empirically. More on this later on in this post, but briefly:

Anki contains 3 of the key concepts of meta-learning: spaced repetition (i.e. seeing something tomorrow, then 3 days away, then 7 etc (rather than “massed” repetition i.e. cramming), active recall (you have to recall things from memory rather than say rereading from your notes), and interleaving (cards are typically all mixed up to keep you on your toes, so you’ll engage with a bunch of different topics/ concepts, i.e. for me it’ll be a mix of coding then geography then history then EA stuff etc). Unlike physical flashcards, the exact right flashcards to review for the day are automatically presented to you, and there’s no chance that you’ll forget or remove a flashcard once you think you’ve mastered it: the algorithm handles everything for you.

Now we’ve got that quick primer out of the way, here’s what Make It Stick says about knowledge and learning and how Anki is perfect for it.

What is learning, knowledge, intelligence?

What I’m aiming to do with this post is demonstrate to people that Anki isn’t just about memorising key facts - it’s actually about learning, increasing your knowledge, and intelligence.

As such, I’ve collected a bunch of relevant quotes from the book Make It Stick (amongst other sources) below.

Learning: a three-step process

According to Make It Stick (credentials for the book/ authors, see here[3]) (which I’ll henceforth refer to as MIS), learning is at least a three-step process:

-

Initial encoding of information is held in short-term working memory before being consolidated into a cohesive representation of knowledge in long-term memory.

-

Consolidation reorganizes and stabilizes memory traces, gives them meaning, and makes connections to past experiences and to other knowledge already stored in long-term memory.

-

Retrieval updates learning and enables you to apply it when you need it.

Here’s a pattern that I’m going to be repeating a lot: concepts pulled from MIS re: learning, followed by examples of how Anki perfectly aligns with how to act on these concepts.

So here we go: when we’re aiming to learn, i.e. whilst reading non-fiction, the initial encoding (step 1) is done as we get to grips with the information. The act of making a flashcard is a form of active encoding, whereby we need to give further meaning, & make connections to other things we know (step 2: consolidation). Once the card is made, when it appears in our queue, we have to actively retrieve the information, further strengthening the knowledge.

Relevant Michael Nielsen quote from here: “making Anki cards is an act of understanding in itself. That is, figuring out good questions to ask, and good answers, is part of what it means to understand a new subject well….’The act of constructing an Anki card is itself nearly always a form of elaborative encoding. It forces you to think through alternate forms of the question”

Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning

Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning is a well-known 1956 framework for understanding learning. Below I’ll briefly expand on the 2001 revised version, to demonstrate how learning is typically characterised and how Anki can contribute to deep learning.

The 2001 version outlines 6 categories of learning, in increasing order of complexity, and 4 types of knowledge.

Bloom 2001: The 6 Categories of Learning

- Remember

- Understand

- Apply

- Analyze

- Evaluate

- Create

As I’ve previously argued, Anki is fantastic for ensuring you remember, but also the act of creating a card ensures that you’re more deeply engaging with the content, and therefore that you understand it. As Nielsen said above, you have to understand the content in order to ask good questions. This therefore covers at least the first 2 categories of Bloom’s taxonomy.

There’s the idea of “fluency” of thought, which relates to “the sense of ease or speed of processing; fluency during the retrieval of information is the sense of how readily information “comes to mind.”[4] Anki is fantastic for this: as you repeatedly engage with a concept via spaced repetition and active recall, the concept gets more embedded and internalised, and easier to fluidly recall. I’d argue that this helps a great deal with the further categories of learning from Bloom’s taxonomy: the ability to fluidly recall information and concepts allows you to analyse other similar concepts by making comparisons, to create new insights by combining, etc, on the fly i.e. without needing to consult notes.

MIS on the need for foundational knowledge for higher level things like creativity: “Pitting the learning of basic knowledge against the development of creative thinking is a false choice. Both need to be cultivated. The stronger one’s knowledge about the subject at hand, the more nuanced one’s creativity can be in addressing a new problem. Just as knowledge amounts to little without the exercise of ingenuity and imagination, creativity absent a sturdy foundation of knowledge builds a shaky house.”

And similarly, on the concept of mastery:

“Mastery in any field is a gradual accretion of knowledge, conceptual understanding, judgement, and skill… These are the fruits of variety in the practice of new skills, and of striving, reflection, and mental rehearsal… Memorising facts is like stocking a construction site with the supplies to put up a house… Mastery requires both the possession of ready knowledge and the conceptual understanding of how to use it”

Bloom 2001: The 4 Categories of Knowledge

- Factual knowledge

- Lowest level

- Knowledge of terminology, specific details, elements

- Conceptual knowledge

- Knowledge of classifications and categories

- Knowledge of principles and generalisations

- Knowledge of theories, models and structures

- Procedural knowledge

- Knowledge of subject-specific skills and algorithms

- Knowledge of subject-specific techniques and methods

- Knowledge of criteria for determining when to use appropriate procedures

- Meta-cognitive knowledge

- Strategic Knowledge

- Knowledge about cognitive tasks, including appropriate contextual and conditional knowledge

- Self-knowledge

It’s clear to me that Anki works for at least the first 3 of these. Each subsequent category here really seems to represent an increasing complexity & cumulation of the lower levels. For example, Anki can be used to learn the basic facts of a field (level 1). These can then be used to get to grips with higher level concepts like categories, overall theories, and principles. These can then be used to create higher level techniques, procedures etc.

This layering of complexity represents the idea of cumulative learning. MIS re: cumulative learning: “so that retrieval practice continues and the learning is cumulative, helping students to construct more complex mental models, strengthen conceptual learning, and develop deeper understanding of the relationships between ideas or systems.”

Michael Nielsen quote re: importance of learning the basics:

“My somewhat pious belief was that if people focused more on remembering the basics, and worried less about the “difficult” high-level issues, they’d find the high-level issues took care of themselves.”

This also matches perfectly with what Nielsen described re: his experience using Anki to gain a durable and deep understanding of a brand new field to him. learning complex new field:

“With a few days work I’d gone from knowing nothing about deep reinforcement learning to a durable understanding of a key paper in the field, a paper that made use of many techniques that were used across the entire field”

“I began with the AlphaGo paper itself. I began reading it quickly, almost skimming. I wasn’t looking for a comprehensive understanding. Rather, I was doing two things. One, I was trying to simply identify the most important ideas in the paper… Second, there was a kind of hoovering process, looking for basic facts that I could understand easily…”

“After five or six such passes over the paper, I went back and attempted a thorough read… After doing one thorough pass over the AlphaGo paper, I made a second thorough pass, in a similar vein. Yet more fell into place. By this time, I understood the AlphaGo system reasonably well. Many of the questions I was putting into Anki were high level, sometimes on the verge of original research directions…‘”

Also it seems that this is very relevant to how a Medicine student will use Anki: first learning the essentials, and over the years developing an understanding of when to use appropriate procedures etc, i.e. a more all-encompassing level of knowledge.

Inert vs activated knowledge / accessible vs available information

Something that I came to realise after I switched my learning meta to be primarily about making notes in Obsidian was that I had unconsciously shifted my focus from activated to inert knowledge. I was making lovely interconnected notes, but the knowledge in these notes wasn’t “activated” in my brain: if you took my notes away, I couldn’t recall the key points at will. This is where Anki is far more useful: by internalising key facts and insights (for example, I’ve made flashcards from part 1 of Toby Ord’s The Precipice), you can now use these facts in your day-to-day thinking, perhaps explaining to a friend one of Ord’s points, or thinking about it whilst walking the dog (if you’re anything like me), or using it whilst writing something like this without a) having to check your notes or b) not using at all because you forgot the relevant fact even existed.

MIS quote: “The situation where information still exists in memory yet cannot be actively recalled has been emphasized as a key problem in remembering (Tulving, Cue dependent forgetting). Stored information is said to be available, whereas retrievable information is accessible. The instance we give in this chapter of an old address that a person cannot recall but could easily recognize among several possibilities is an example of the power of retrieval cues in making available memories accessible to conscious awareness. ”

Prior knowledge as foundation for new learning

MIS: “Learning always builds on a store of prior knowledge. We interpret and remember events by building connections to what we already know.”

“All new learning requires a foundation of prior knowledge. You need to know how to land a twin engine plane on two engines before you can learn to land it on one. To learn trigonometry, you need to remember your algebra and geometry. To learn cabinetmaking, you need to have mastered the properties of wood and composite materials, how to join boards, cut rabbets, rout edges, and miter corners.”

Therefore, using effective meta-learning strategies like Anki ensures that you can remember the foundations for the long run, making further learning easier.

This highlights the idea of “orphan cards” in Anki. A common & ineffective strategy is to make cards that don’t really tie to anything else in your mind. For example, I wanted to remember that Monte Carlo was the capital of San Marino. I made this card, but really struggled to get it right. It turns out this is because I had literally 0 other pieces of information about San Marino in my head to tie this fact to. By making just a few more cards covering things like “where on a map is San Marino”, “what is the population of San Marino”, etc, I now had a more complex and “sticky” web of knowledge, making this far easier to remember.

When learning a new field, you often have very little pre-existing knowledge to work with. Anki means that you can immediately start building out a web of the basics, which makes further learning far easier.

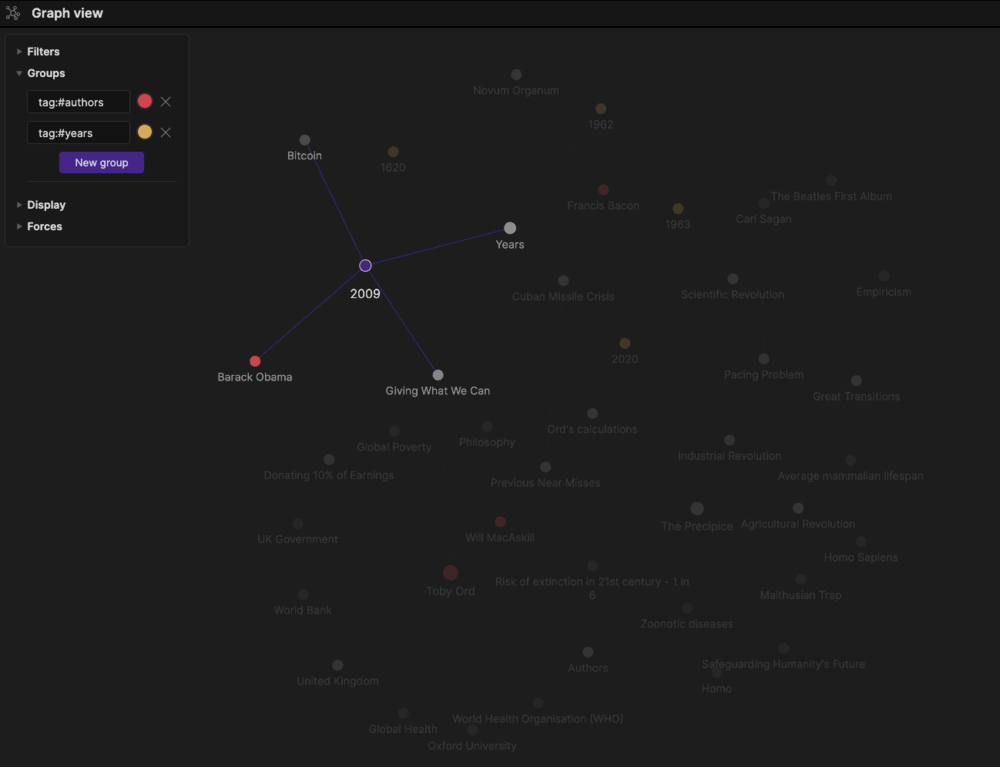

(Obsidian’s graph view of notes can be used for a visual representation of this. I was struggling to remember that Giving What We Can was founded in 2009, but after adding the extra facts that Obama became President & was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, & Bitcoin was founded in 2009, the year of GWWC’s founding became far easier to recall)

Obsidian graph view to demonstrate idea of interconnecting web of knowledge - the more connections, the easier something is to remember. Cards with very few / only 1 connection are termed “orphan cards”

Intelligence?

According to MIS, it is generally accepted that there are at least 2 kinds of intelligence.

Fluid intelligence

Ability to reason, see relationships, think abstractly, hold information in mind while working on a problem

Crystallised intelligence

Accumulated knowledge of the world & the procedures or mental models one has developed from part learning and experience.

It’s therefore very easy to see how Anki can aid with crystallised intelligence, as it allows you to build a cumulative knowledge base over time. This knowledge base in time also helps you to reason (for example, if you used Anki to learn the core cognitive biases and then used this information to fluidly assess your thinking day-to-day).

Getting started with Anki

Post 3 is a concise guide to using Anki including the key patterns to use, things I wish I did from day 1, things to avoid etc. See you there!