(Lack of) learning at school -> empirically backed best ways to learn -> profundity of memorisation -> Anki & benefits.

Original publish date: 2021-08-17

2021-09-11 quick note - highly recommend checking out this episode of the Clearer Thinking podcast with Andy Matuschak (who I mention on the resources page) for a fantastic primer on meta-learning / spaced repetition

Summary

learning at

school) id2(Best ways to learn) bwtl1(Spaced

repetition) bwtl2(Active

recall) bwtl3(Active

encoding) id3(Anki) id4(Profundity of

memorisation) prof(Harold

Bloom) id5(Benefits

of anki) boa1(Learning

doesn't

degrade) boa2(Incremental

reading) boa3(Growth mindset

and belief in

ability to learn) id1 --> id2 id2 --> bwtl1 id2 --> bwtl2 id2 --> bwtl3 bwtl1 --> id3 bwtl2 --> id3 bwtl3 --> id3 id3 --> id4 id4 --> prof id4 --> id5 id5 --> boa1 id5 --> boa2 id5 --> boa3

Learning at school & higher education as I experienced it

I remember being an A-Level student and having absolutely no idea how to effectively study. At GCSE, I found a fair amount of subjects simple enough to cover without much work: Maths felt quite intuitive, the Sciences were drilled into us enough in class that there wasn’t much to try harder to retain, our German classes were rigourous enough that revision was just a case of going over things that were already fairly internalised. Looking back now it’s definitely clear that sheer amount of time we spent in classes with teachers overseeing the learning made actual mechanics of the learning far easier: there’s no need for self-directed studying when you have a learning tutor drilling things into you (ok that sounds weird!).

A-Levels followed much the same mould, although I remember a few times when exams were getting closer where I felt overwhelmed with the amount that needed to be remembered, especially in things like Biology and Chemistry where you need to recall certain structures and acronyms (whereas for English Literature and Psychology there was more room for creativity as long as the basics were remembered).

It’s a fairly trite and well-known observation that university requires far more self-directed learning. In fact, it requires almost 100% self-directed learning. You no longer have hours with teachers who are overseeing a relatively small group of students: it’s now (at least on my course) 1 to 2 hours per lecturer per week, in a group of >100 students, and the method of teaching switches dramatically, from some theory followed by exercises and feedback, to hours of one-way lectures^^1, where participation is theoretically encouraged but the mechanics of the set up (being in such a large group, having to raise your voice to be heard, fear of stammering etc) means you’re far more inclined to remain quiet. Your new task is to stay focused for an hour or more, and working out a way to actually learn on your own. Do you take diligent notes (or even record the lecturer), take only select notes and try hard to critically engage with their points as they talk, or scroll through Reddit and Instagram after the first 10 minutes?

And once the lecture is over: do you rewrite all your notes, or transcribe what the lecturer said, or read a relevant textbook chapter or the recommended reading provided in the final Powerpoint slide?

I now know the answer to these questions, but for the whole of my Undergraduate degree and most of my Masters, I had absolutely no clue, and used profoundly wasteful and flawed methods in an attempt to learn. As a result, I can literally recall almost nothing I was taught, and I suspect this is the same for virtually all university students a few years after graduating. It’s a universal feeling: studying hard for exams, the summer holidays happening, and feeling like you’ve forgotten every single thing.

The great news is: there’s a much better way. And even better: it’s straightforward, free, and extremely powerful. It will allow you to remember what you’ve learned for the rest of your life, engage more deeply with what you’re currently studying, and improve your life in myriad other ways if you expand what you want to learn outside of your specific field (for example, by hugely increasing your retention of history books, or improving your world geography knowledge, learning a new language etc). Perhaps most importantly of all, it’s not just about memorisation of facts: it helps you build knowledge in your chosen field of interest, helping you capitalise on whatever you’re trying to learn, fluently recalling information and using it creatively to solve problems and create connections.

The best way to learn

I’ll jump straight to the chase here (I have a lot of notes on the inefficient methods most students use for studying, but I think it’ll be better to jump straight to the valuable and actionable information for the time being).

The two key (and one bonus) science-backed ways to learn

There are two techniques for learning that have been rigorously tested and shown to work wonders. Stick around as the fantastic news is that there’s a free tool that packages these techniques into one package.

The first: active recall. This is a very simple technique and one that I didn’t use at all at GCSE, A Level or Undergraduate. It’s illustrated in this example: reading a page of a textbook, or a few slides from a Powerpoint, then looking away, and seeing how much you can remember. We’ve all had the experience of making beautiful notes that are colour coded, neat and packed with diagrams. This often makes us feel like we’ve accomplished a lot in our study session. However, the true test of our knowledge is what we remember once someone takes those beautiful notes away. If we find that we can’t remember all that much, then this naturally doesn’t bode well for our exams. And even more so, for the rest of our lives, as we’ll be able to get through exams with a hefty amount of cramming, but as soon as this is over, we’ll be left with nothing in our brains for use after our degree is over.

Therefore regularly testing ourselves when away from our notes (or when the textbook has been briefly shut) is a great way to assess our level of knowledge, and to actually strengthen the knowledge in our brain. Each time we actively recall some information (like the capital of Romania), we actually strengthen those neural connections, making it easier the next time around.

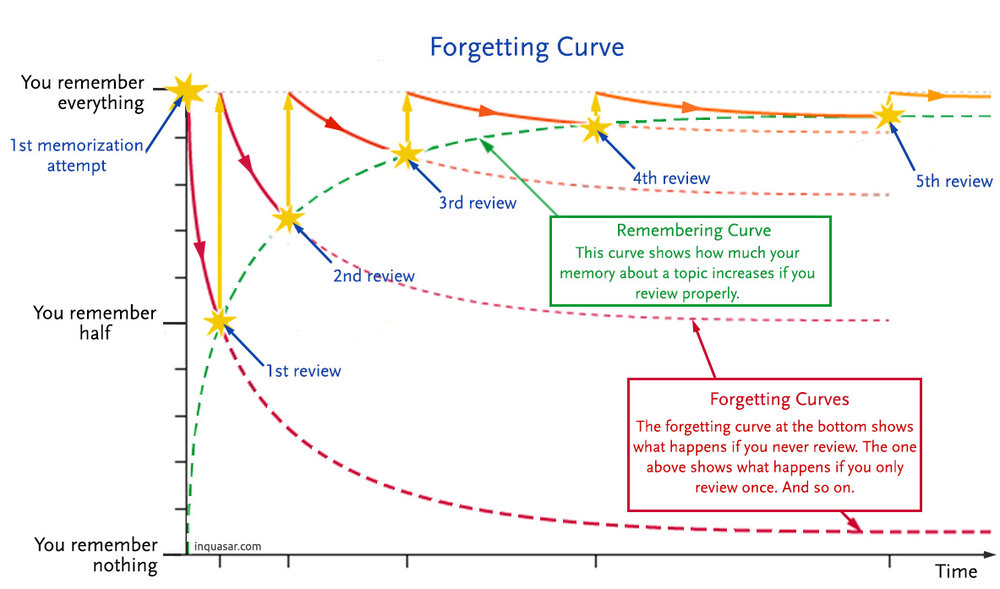

The second one: spaced repetition. This is the principle whereby it’s better to study in a spaced-out manner than all in one go. For example, rather than trying to recall a newly learned fact 10 times in one day, it’s better to look at it once the first day, then again the next, then again in 3 days, then in 5, etc etc. This has been backed by science.

And the really fantastic news is that both of these principles are used in the main tool I’ll be talking about for learning, the free, open source software that makes both active recall and spaced repetition a guaranteed practice when used every day: Anki.

As a bonus, a well-known method for learning is “active encoding”. This is well known but requires effort to implement: it involves actively engaging with what you’re attempting to learn. This could involve taking what you’re learning and thinking how it relates to other things you know, devising memorable mnemonic devices to make things stick in your brain (for example “Richard of York Gave Battle in Vain” for the colours in the rainbow), or thinking of further questions (i.e. “that’s interesting, I wonder if the P45 gene can be influenced by epigenetics?”).

(For a great primer on active recall & spaced repetition, check out this Ali Abdaal video)

Anki

Put simply, Anki is a flashcard tool. I remember making paper flashcards at Univeristy, and they worked pretty well. However, using a digital tool has some huge advantages.

First of all, it’s way quicker (and cheaper). There are no materials, no writing with a pen. You can quickly make cards, and can end up with hundreds or thousands, without carrying a stack of dog eared cards around with you.

Second, the spaced repetition element is baked in in a way that would be far harder to implement with paper cards. For every flashcard you answer, you quickly score how easy it was to recall. If the information was recalled easily, the algorithm takes this into account. For example, if I made a card a few days ago and this was my second day in a row of seeing it, if I found it easy to recall, I won’t see it for another 3 days. If when I see it again it’s still easy, it’ll be 7 days until I see it. If in 7 days it’s still easy, I won’t see it for 14 days. I have cards coming up now which I still find easy to recall, and which therefore won’t be seen for another 2 years. Imagine trying to implement this with paper cards!

On the flip side of this point, if a card pops up and I’ve totally forgotten it (for example the date of the Battle of Trafalfar), I can mark it as “hard” by hitting the 1 key on my laptop, and this card will show up again tomorrow. This means that things that you may have totally forgot forever instead get reintroduced into your learning inbox, allowing you to reengage with them and add them back into your repertoire.

It’s worth quickly mentioning that Anki also has active recall baked in. You’ll typically make flashcards in a question and answer format (i.e. Q: “What is the capital of Romania?” A: Bucharest), and therefore when you see the question, you have to actively search your memory for the answer. Therefore along with spaced repetition, Anki has both of the key methods for learning baked in. It’s fantastic.

In fact, it even has the bonus technique baked in (active encoding)! The creation of a flashcard is in itself a form of active encoding. You’re having to engage with the information in order to generate a useful flashcard, for example rearranging a statement from a lecturer into a question, or drawing connections between two ideas (i.e. “P45 is a cancer-regulating gene, similar to __”)

The profundity of memorisation

Memorisation (or rote learning) is somewhat maligned in our educational culture. I found that at University we were rarely told to go away and memorise definitions. I suspect that a large part of this was due to a lack of knowledge in the general population (and my lecturers) that easy memorisation is possible: it’s not even known as a thing that can be done, so you’re not going to get lecturers casually saying “before next week go away and memorise each gene I mentioned this week as it’ll be really helpful for the next lecture”. However, it’s my belief that memorisation is dramatically important in learning. A few different concepts come into play here.

First, and potentially most importantly, is the idea of “fluency”. Put simply, fluency is the speed to which things come to mind. For example, if you are attending a lecture on the biology of cancer, and you haven’t learned & memorised the basics, it will be far harder to follow along. The lecturer will mention the P45 gene, and you’ll have a vague idea that this is important for cancer, but won’t be able to recall the details. You therefore won’t be able to follow their points as they’re building on information that they’re assuming you internalised from last week’s lecture, as they happened to mention them last week. If instead you have memorised the basics, you’ll be “fluent” in these bits of terminology, and as soon as P45 is mentioned you’ll be able to engage with what the lecturer is talking about on a much deeper level and have stronger mental hooks to hang the new information they’re giving you^^2.

The second part of why memorisation is profound: when you have something memorised, you can recall it at will, for example whilst thinking on a walk or studying a related topic. This is now part of your mental interior and you can use it on the fly. In a lecture, this could manifest in a lecturer mentioning a certain gene and you remembering a similar gene and wondering how they interact. At work, it could be that whilst brainstorming a solution to a problem, you remember how a similar thing was worked out. In a conversation, it could be recalling a similar thing to what your friend is talking about in a book you read.

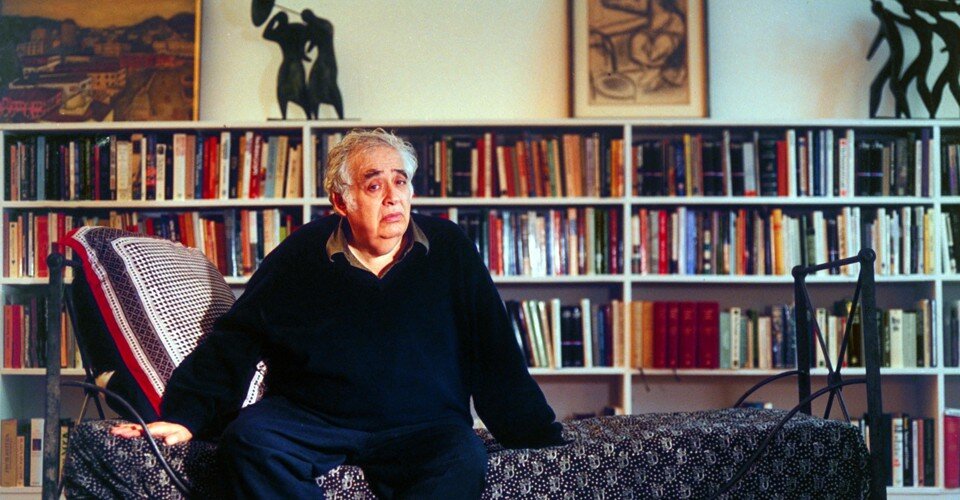

Quick aside: the great literature critic Harold Bloom on the profundity of memorisation

(From an interview with Charlie Rose. Whilst Bloom is talking about memorisation of poetry here, I think what he is saying applies perfectly: memorisation changes and empowers you)

“We lost a great deal in education when we stopped teaching to memorise. Obviously to repeat something by rote without understanding it does no good. But to possess something by memory, to really read a poem hundreds of times because it can sustain hundreds of readings… to hold in your heart and your memory”

“I think if you possess a poem by memory then it begins to possess you. It alters you, it changes you.”

I would argue that this is exactly the same as with knowledge work. To truly internalise a topic or concept, to be able to fluently use it in your day-to-day life, greatly improves your ability to think creatively and engage with work more deeply.

Benefits of Anki as a primary method of learning

Learning that doesn’t degrade with time

One of the most profound benefits of Anki is that it allows you to learn in a way that doesn’t degrade with time. There’s the famous “Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve”, which shows how new memories degrade over time. With Anki, which employs spaced repetition and active recall, this forgetting curve can be overcome, allowing you to for example foundational concepts from the first year of University in subsequent years, a huge benefit to acquiring further knowledge. The normal process is for the first year foundations to become wobbly over the summer break: ensuring they remain deeply internalised is a huge benefit. Imagine a PhD student who could remember all the key concepts taught at every year of their higher education

Incremental reading

Tightly related to the above point (in fact it’s basically the same point): as it’s possible to remember anything you want & to stop memories from degrading over time, the possibility of “incremental reading” is unlocked. This is simply the ability to for example read one chapter of a non-fiction book or textbook, make flashcards from the content, and then come back weeks or months later to continue at chapter 2, at which point you’ll still have a strong understanding of the preceding chapter. In fact, you’ll understand it better than when you first read it, as the spaced repetition and active recall means that the chapter 1 information is now fully internalised and available for fluent use in your brain. I had a “year of reading” where I read 54 books, however I can now remember next to nothing from those books, meaning it was pretty much a total failure. Using incremental reading is the solution to the classic thing where you read a non-fiction book and barely remember anything from it.

Growth mindset and belief in ability to learn

Another incredible benefit is the huge self-esteem boost and natural shift to a “growth” mindset from Anki. Once it becomes clear how easy Anki makes the learning process, new topics and fields that once seemed impenetrable now become far more accessible: you realise that learning a new field is as simple as gradually creating Anki cards which allow you to internalise the basics, which in turn let you further internalise more advanced concepts, etc.

Further Anki details & how to use it well

A few quick notes on why Anki is great:

- Free

- Effectively implements the 3 key learning techniques (active recall, spaced repetition, active encoding)

- Large community (reddit.com/r/anki)

- It is available on most devices (Windows, Mac, Linux, iOS & Android (that must be basically every device))

- It has syncing between devices

- It has community made addons

How to use Anki well

This will come in further posts!

You’re now ready & encouraged to download Anki and get stuck in.

One thing I’m excited about with this site is sharing the patterns & antipatterns of Anki use to help people hit the ground running, letting them create excellent cards immediately. As I iterated over my Anki flashcard creation process over years, I still see cards every day that were made early on and are very poorly done, being far less useful than they could have been. I therefore want to clearly outline the biggest best practices to help people avoid these mistakes and maximise their Anki usage early on.

Anki flashcards to use from this post

This may be totally jumping the gun as a) I haven’t outlined how to download & use Anki yet and b) I mentioned that creating your own flashcards is best as it’s a guaranteed way to perform active encoding, but I wanted to include some ready-made cloze-deletion flashcards here so people can start internalising the core concepts straight away.

One benefit of doing this at the end is that hopefully you’ll now have read the whole post, and will understand these flashcards. A typical issue with getting flashcards from other people (i.e. shared decks on Anki) is that you didn’t see the same source material and don’t have much of a grounding in the flashcards, whereas here I’m just ankifying things you’ve now read.

Try adding the following flashcards to your Anki, reviewing them daily for a few days, then coming back to this post. You’ll find that you’ll have internalised these basic concepts!

The two vital techniques for effective learning are {{c1::active recall}} and {{c2::spaced repetition}}

The two vital techniques for effective learning are {{c1::active recall}} and {{c1::spaced repetition}}

In addition to {{c1::active recall}} and {{c1::spaced repetition}}, a bonus learning technique is {{c2::active encoding}}

Put simply, {{c2::fluency}} in thinking is {{c1::the speed to which things come to mind}}

{{c1::Incremental reading}} is the process of {{c2::reading one part of something (i.e. chapter 1), creating flashcards, reviewing those flashcards over a week or so, then coming back and reading chapter 2, etc}}

What is the process of {{c1::incremental reading}}?

{{c2::Reading one part of something (i.e. chapter 1), creating flashcards, reviewing those flashcards over a week or so, then coming back and reading chapter 2, etc}}

Main benefit of incremental reading: {{c1::Means that when you return to next chapter, you’ll have thoroughly internalised the knowledge from chapter 1}}