Everything you need to start strong with Anki!

Summary

Anki) id1_1(Free on

Desktop) id1_1_1(Recommend

starting here) id1_2(Free on Android) id1_3(Paid on iOS) id2(Using

Anki) id2_1(Making

cards) id2_2(Reviewing

cards) id2_3(Home page) id2_4(Creating

a deck) id2_5(How many

new cards

per day) id2_6(Anki as

daily habit) id3(Tips for

starting

strong) id3_1(Cloze

cards) id3_2(Make cards

in plain

text files!) id3_3(Don't make

orphan cards) id3_4(Master deck

with subdecks) id3_5(Make it

clear what

the card

is about) id3_6(Make it

memorable) id4(20 Rules

for Formulating

Knowledge) id4_1(First

understand) id4_2(Start with

big picture) id4_3(Simplify) id4_4(Mnemonic

techniques) id4_5(Optimise

wording) id1 -.-> id1_1 id1_1 -.-> id1_1_1 id1 -.-> id1_2 id1 -.-> id1_3 id1 ==> id2 id2 -.-> id2_1 id2 -.-> id2_2 id2 -.-> id2_3 id2 -.-> id2_4 id2 -.-> id2_5 id2 -.-> id2_6 id2 ==> id3 id3 -.-> id3_1 id3 -.-> id3_2 id3 -.-> id3_3 id3 -.-> id3_4 id3 -.-> id3_5 id3 -.-> id3_6 id3 ==> id4 id4 -.-> id4_1 id4 -.-> id4_2 id4 -.-> id4_3 id4 -.-> id4_4 id4 -.-> id4_5

Intro

Hi there!

In my first key idea posts, I made the case that learning how to learn is a vital skill, debunked the idea that Anki is just for memorising facts, and explored how Anki can be used to create long-lasting and comprehensive knowledge.

In this post, I want to cover everything you need to know in order to start using Anki, and crucially, to start using it effectively. It’s very easy to get started whilst making some key mistakes (which I did for a few months!). I want to mention the essential things to do and avoid.

You can totally get stuck in with Anki without reading this guide, but if you’re anything like me you’ll spend some time making semi-useless cards that’ll make you curse your past self when they appear in your queue down the line!

I’m keeping in mind the Pareto Principle when writing this guide: 20% of Anki’s features lead to 80% of the gains. I’m therefore aiming to keep this guide short and only covering the absolute essentials.

As Michael Nielsen said in his amazing “Augmenting Long-Term Memory”:

“…when someone is getting started I advise not using any advanced features, and not installing plugins. Don’t, in short, come down with a bad case of programmer’s efficiency disease. Learn how to use Anki for basic question and answer, and concentrate on exploring new patterns within that paradigm…”

Downloading Anki & pricing

Anki has both desktop and mobile apps and can be downloaded here. I personally use it almost exclusively on desktop, as it’s far easier to make cards on desktop, and I find I’m more focused when sat at my desk than say in bed with the app on my phone.

A quick note on pricing: it’s free for Desktop and Android, and $25 for the iPhone app (due to different dev teams). I’d say it’s 1000% worth getting the mobile app, but it also makes sense to develop the habit via the free desktop app first. Test the waters before making an investment!

Anki is open source, which is essential as you don’t need to worry about a company folding and losing all your knowledge (I moved from Roam Research to Obsidian for note taking partly for this reason). Open source also means it’s under active development with regular updates, there’s lots of community support, an ecosystem of desktop add-ons, etc.

The actual process of using Anki

The process of using Anki has two parts:

-

Making flashcards

-

Reviewing flashcards

You’ll typically spend much less time making flashcards than reviewing flashcards.

For example, if you make flashcards for 30 minutes, these will then be ready to review the same day. If you say they were easy to recall, they’ll appear again tomorrow, then in 4 days, then in like 10, etc. So a single session of making leads to multiple occurrences of reviewing. This is nice as it means you can spend some time on one making session, then sit back for a week as the reviewing sessions ensure you thoroughly learn the new material.

In this way, if you don’t make new cards, your daily pile to review will gradually shrink (provided you can remember them), as they get more spaced out.

A note on your daily queue: the algorithm works out which cards are due today. I’ve got 11,000 flashcards overall, but today there are only 70 due to review - it normally takes me 5-10 minutes a day to do the whole day’s queue.

The interface: home page

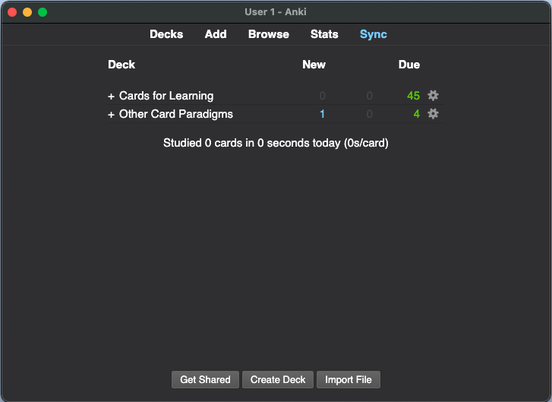

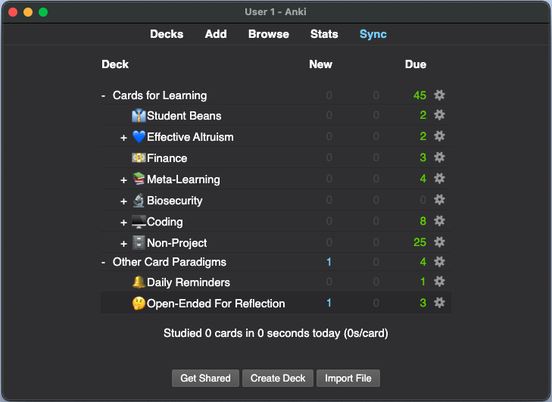

When you open Anki, you’ll see the home page, which shows all the decks that you have, and also a count of how many are due. Brand new cards are shown in blue, and ones you’ve seen before are green.

As mentioned, your flashcards can be organised into decks, which I highly, highly recommend. I wish I’d done this since day one for one main reason: I’ve made flashcards on topics I’m no longer interested in (i.e. I tried to get into football and learned all the managers, key players etc), and it’s been tricky for me to get rid of them: whenever they appear in my daily stack, I delete them as they pop up. It’d be much cleaner to just be able to delete them all in one go. In addition, you might have a deck of cards related to your job, and when you leave that job you’ll be able to delete them and not have them periodically appear in your queue.

The argument I’ve seen for having one single deck is the idea of “interleaving”, which appears in the academic literature on learning as a way to increase learning. This is where your queue is full of multiple topics, i.e. you’ll answer one question about geography, then history, then coding etc. This “all mixed in together” approach has some evidence for increasing learning.

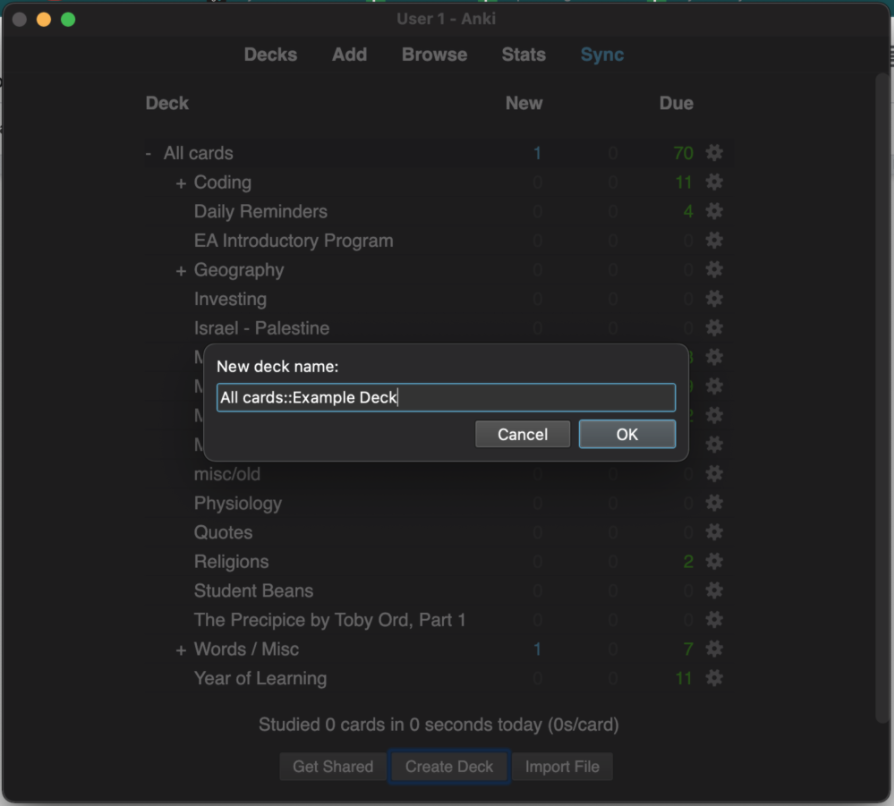

It turns out, you can have your multiple-decks cake and interleave it too, by simply creating one master deck (you can see that mine is called “All cards”), and then have every other deck be a subdeck of this one. For example, if I wanted to make a deck for coding, I’d just have to call it “All cards::Coding”, and Anki will understand that this is a subdeck. Then I can click on the master deck and hit review, and the review pile will contain all the due cards from all the subdecks. Lovely!

My master decks: you can see that I have 45 non-new cards to review in my “cards for learning” master deck, and 1 new card + 4 to review in my “other card paradigms” master deck.

I’ve un-collapsed my master decks and you see all the subdecks that sit underneath. Some of these have cards due, some don’t.

Creating a deck

To create a new deck, you guessed it! Press the “create deck” button. Make sure to make a master deck and then have any subsequent cards be subdecks.

When creating a new deck, use the format {Master deck name}::{New deck name}

Making cards

There are two basic card types that I’m aware of: “Basic”, and “Cloze”. 99% of my card types are cloze types, and they’re the ones I recommend using.

Cloze (or cloze deletion) cards are essentially fill-in-the-blank cards, and are particularly quick to make.

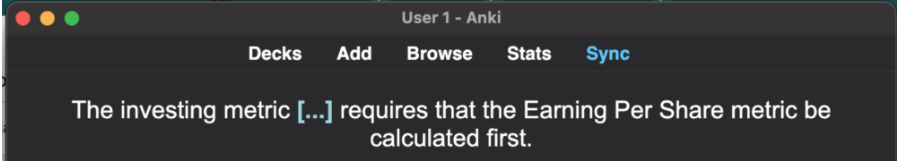

Here’s an example card:

The investing metric {{c1::P/E ratio}} requires that the {{c2::Earning Per Share}} metric be calculated first.

This will generate two cards: one with the first curly braces missing and to be guessed, and one with the second curly braces missing and to be guessed.

If I had instead done this:

The investing metric {{c1::P/E ratio}} requires that the {{c1::Earning Per Share}} metric be calculated first.

Both of the curly braces would appear blank at the same time.

As I’ll discuss below, I highly recommend making your flashcards in a text file, rather than directly in Anki, but we’ll get to that later!

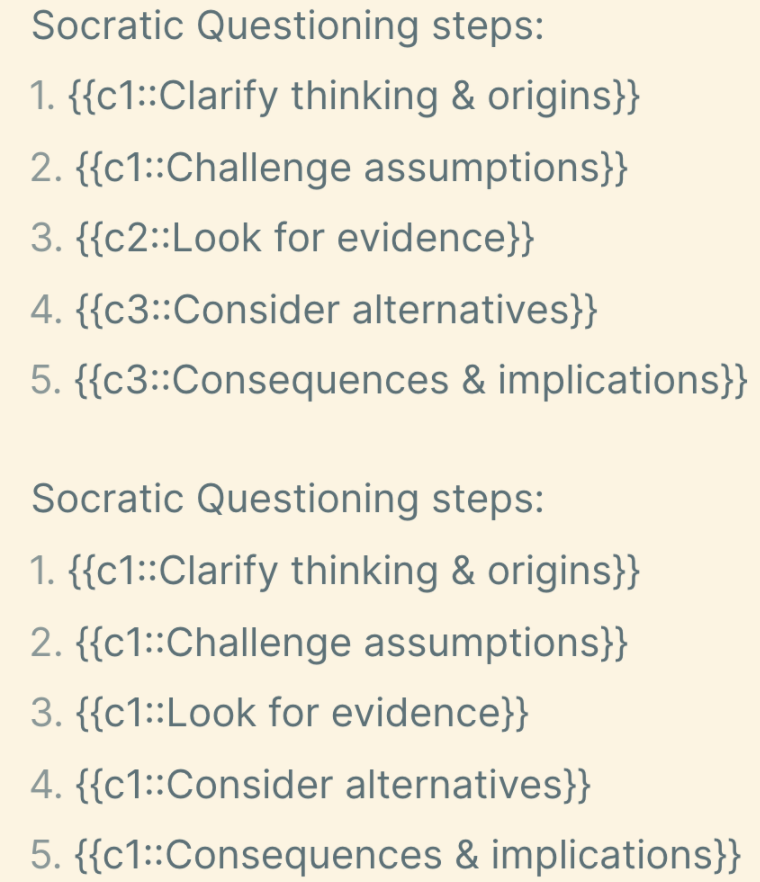

One reason I really like cloze is you can quickly make multiple variants of the same card. The below screenshot shows what I mean. Here, I’m learning the 5 steps of Socratic Questioning. I first make a card with c1, c2 and c3 clozes, meaning this card will produce 3 separate cards, making it easier for me as I don’t have to remember all 5 blanks at once. I then make the same card, but change all clozes to c1, so that I will have to guess all 5 blanks. I make the first card to make learning it easier, and then the second card as a way to increase the difficulty.

Cloze deletion lets you quickly make variants of the same card. Here, I’ll have one card what has three separate “fill in the blanks”, where only one appears blank at the time, and then I have another card where all 5 will be blank at the same time, to increase difficulty.

Settings for how many new per day

For each deck that is made, you can set the number of new cards you want to see each day.

The default is 20 new cards per deck. This may work for you, but if you find you’re being overwhelmed, you can reduce the number.

For example I have a vocabulary deck that I downloaded (which I’d highly recommend!), which I have set to only show me 1 a day, as I’m in no rush with it, and I find a single new word is a day is a good pace.

Medical students will often set their decks to show the max amount of new cards per day as they literally have so much to remember.

A key benefit of making a master deck is that you can use it as a bottleneck for the number of new cards to see in a day. I.e. say you have 10 subdecks all set to 20 new cards a day, but you want a break or to slow the pace down: you can set the master deck to be only 10 new cards a day, and you’ll just have 10 new cards per day.

Naturally, the amount of new per day will have an impact on how long you spend on anki every day. If you’re not in a rush I’d say 20 per day for your master deck is enough.

Setting to 0 can also be a good way to create some space if you’ve left it a few days, or if you’ve covered enough new english words for a while and you want to pause that deck for a while

Anki as a daily habit

A quick note that ideally Anki needs to be a daily habit. This is potentially the biggest pain point for the app, as the gains come from keeping on top of it, and if you don’t, your queue will pile up a bit.

I’ve occasionally been on holiday and not done them for a week or more, which typically just means my typical pile of 80 reviews a day builds to 300-400. From here I could either catch up again in one mega-session, or just do a slight excess each day i.e. 120 a day and catch up slowly.

Seeing a big pile waiting for you is a bit of a pain point/ creates some friction, so I would recommend against it, as it might lead to you dropping it altogether or procrastinating it: my partner made loads throughout her first year of uni and now hasn’t reviewed all summer and is too afraid to get stuck back in!

Tips for use: starting strong

Rather than doing a bit of research or reading something like this article, I just got stuck in with Anki, which has lead to some mistakes which I now regret, and I still see a lot of old cards I made which make me cringe and cry.

Here I’ll quickly cover the key things I wish I’d known at the start.

Make your flashcards in plain text files!

This is my number 1 tip and something that I wish I’d have done since day 1. I’ve only discovered this in the past 2 months and it has been a huge game changer.

Essentially, when you add flashcards in one-by-one via the Anki UI, as soon as you create one, it vanishes, and you’re looking at a new blank card. Therefore you quickly forget what you’ve just made, and don’t have a good holistic view of all the cards you’re making on a topic. This leads to you under-creating cards: you can’t see any holes in your current library. This means that your knowledge will also be gap-y.

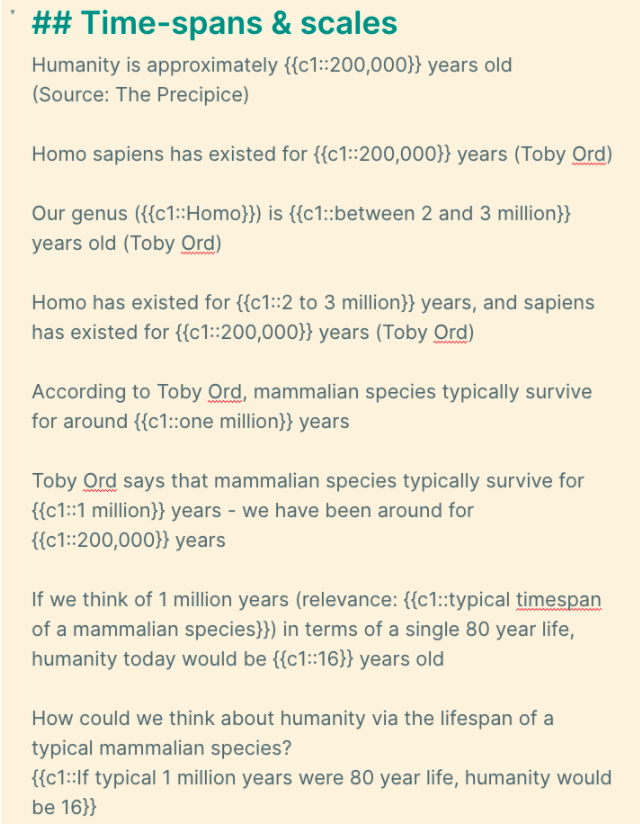

In contrast, if you make your flashcards in a plain-text file, you get a holistic view of all the flashcards. For example, when making my flashcard deck for part 1 of Toby Ord’s “The Precipice”, I could see what had been made, make variants of what had already been made, sort cards under headings by theme, add more cards over time, etc.

This also helps hugely with avoiding making orphan cards (coming up shortly). If you’re making flashcards via Anki’s UI, you can fire them into the ether really quickly, and not really notice if the card you just made is an orphan. If you’re making them in plain text files and organising by theme under headings, it’s much more clear when you’ve made an orphan card, and way easier to come up with some supporting cards to flesh out the idea.

Making the flashcards in plain-text format also makes them easier to share. For example, I’ve been at my new job for 4 months and have been making flashcards about it as I go (business logic, database stuff, outcome from meetings and projects etc), and I’ve been able to chuck them on our team’s Notion page for other people to use.

To quote Andy Matuschak:

Unfortunately, most spaced repetition interfaces treat each prompt as a sovereign unit, which makes this kind of high-level revision difficult. It’s as if you’re being asked to write a paper by submitting sentence one, then sentence two, and so on, revising only by submitting a request to edit a specific sentence number. Future systems may improve upon this limitation, but in the meantime, I’ve found I can revise prompts more effectively by simply keeping a holistic aspiration in mind.

Making flashcards in text files (rather than directly in Anki) gives you a holistic view of all the cards you’ve made, so you can identify gaps, make further ones to expand points etc

Don’t make “orphan” cards

An orphan card is a single card that doesn’t link to any other card, or doesn’t link to anything in your brain.

For example, early on I was really excited to use Anki to learn geography, in particular flags, countries and capital cities.

There are loads of well-made community flashcards for these. However, they’re flawed in a major way: there are no “extraneous info” flashcards to flesh out your understanding of each country/ flag/ city.

For example, if I wanted to remember that the capital of Romania is Bucharest, these decks would contain that fact. However, I need to go a step further and make that info stick to something in my mind. Therefore, I could make a flashcard that said “how do you remember that the capital of romania is bucharest?” “because I need to remain here and book a rest”. It’s now far easier to remember.

Or re: flags - I could try and learn the flag of San Marino, but if I literally have no information about San Marino in my brain, there’s no information for this to stick to. However, if I spend some time reading San Marino’s wikipedia page, maybe watch a youtbue video about it so I can picture it, and I learn that the 3 towers on the flag are on mount titano, I now have multiple san marino “hooks” in my brain that I can attach the flag image to.

Early on, I thought Anki would be a super power that would let me remember anything, so I chucked any old crap in there, particularly things I thought I “should” learn, or that would be useful in some way at some point. However, Anki only works if you have good hooks to hang the info on (and you can create these hooks by creating enough cards on a topic, i.e. the multiple cards about San Marino.)

Resist the temptation to make cards for anything that seems like it might be useful one day, or that don’t serve some kind of project or aim. If you’re like me, you’ll be annoyed at these random cards when they pop us, as they’ll be much harder to get right, and won’t really to adding any meaning to your life.

Master deck, with subdecks if you want

Already said this above, but just to re-iterate! Make subdecks for different topics, all sat under a single master deck. Lets you interleave your learning, and easily delete any topics that you end up wanting to drop.

Make it clear what the card is about

Early on, as I didn’t have many cards (and didn’t know how into this I was going to get), I’d make cards like

{{c1::The cuban missile crisis}} happened in year {{c2::1962}} {% raw %}

Now, for the card “The cuban missile crisis happened in year _”, this is fine. However, say it’s 2 years later and I’ve gotten really into history, and have made loads of flashcards from the 1940s onwards. Now if the card “__ happened in 1962” comes up, it’s a dreadful card, as there could be many answers, i.e. it’s ambiguous.

Therefore, I learned to make sure that the general theme or topic of the flashcard was hinted at: not in a way that gives it away, but that indicates the correct answer. Maybe it does give it away somewhat, but it’s still much better than the previous example.

For example, I could make the card: {% raw %} (Geopolitical event) {{c1::The cuban missile crisis}} happened in year {{c2::1962}}

Recognise when a card won’t be memorable and make extra cards to make more memorable

Some things stick in your mind pretty easily, but some things are much harder, for example dates, names, statistics etc. In these cases, it’s a good idea to make supporting cards to help create a better web of knowledge, so you have more “hooks”.

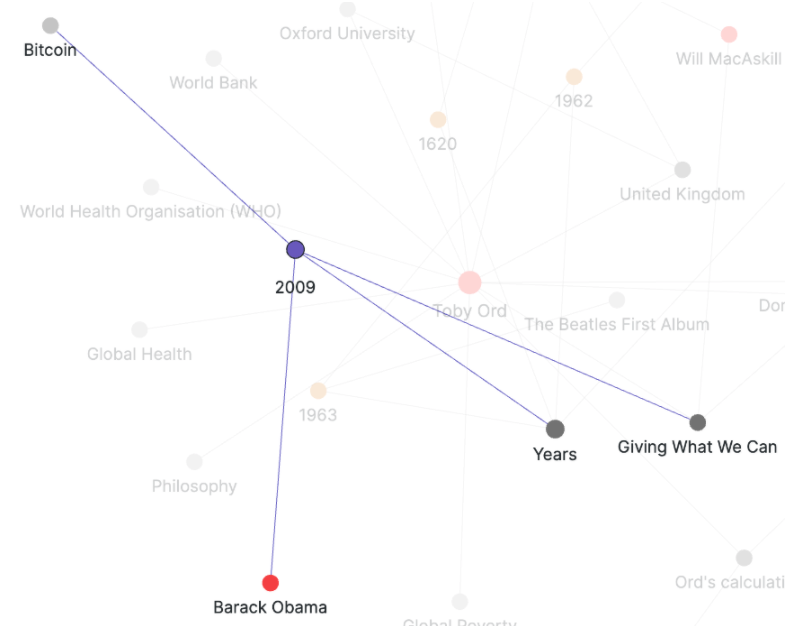

For learning the year when an event happened, something I’ve found really useful is tying a few things that happened in a year together. I wanted to learn that the charity “Giving What We Can” was founded in 2009, so I did a quick Google and found that this was the year Obama became President & got the Nobel Peace Prize, and also the year Bitcoin was created. Now remembering the year GWWC can founded is much easier as I’ve got multiple things hooked to it in my brain. I.e. instead of being an orphan, it’s not got multiple connections.

Other techniques include acrostics and including images.

This graph view demonstrates the idea of avoiding orphan cards nicely. Instead of just trying to learn that Giving What We Can was founded in 2009, I learned some other things that happened in 2009, and now there are multiple connections to this fact in my brain. It’s shockingly powerful and easy to do!

20 rules of formulating knowledge!

The founder of SuperMemo (another “spaced repetition software”) wrote the 20 rules of formulating knowledge, which can also be seen as “20 rules for making good flashcards”.

I’ll quickly go over the best stuff here.

-

First Understand - never memorise something if you don’t understand it first. This is a pitfall you can fall into when using downloaded decks: the person who made the cards read the source material, whereas if you’re trying to learn a new topic, you didn’t get to grips with the concepts first, so the cards will probably be less useful

-

Start with the Big Picture & build on the Basics. Get the basic foundations down first, and then you can add further detail on top. Having a good foundation makes further learning far easier and much more durable.

-

Simplify: you want your cards to be as simple as possible, i.e. it’s much easier to recall a single fact than trying to recall multiple. Complicated cards slow you down and are harder to learn.

-

Use mnemonic techniques. Acrostics like “Richard of York Gave Battle In Vein” are really powerful. For example, I’ve got “Naked Cowgirls Lick Asda Groceries” to make remembering that the New Economic Forum’s Five Ways To Wellbeing are Notice, Connect, Learn, (Pay) Attention, Give. Using a memorable mnemonic device lets you create a single “chunk” from multiple items.

-

Optimise wording. Make sure the wording in your cards is clear, so it’s clear what the answer could be. For example, “Martin Luther King died in (year) {{c1::1968}}” has the hint (year) so you know exactly what the cloze deletion is looking for.

And that’s it! Enjoy!